When I first heard about slab climbing, I was shocked to hear how many climbers are hesitant to try it out.

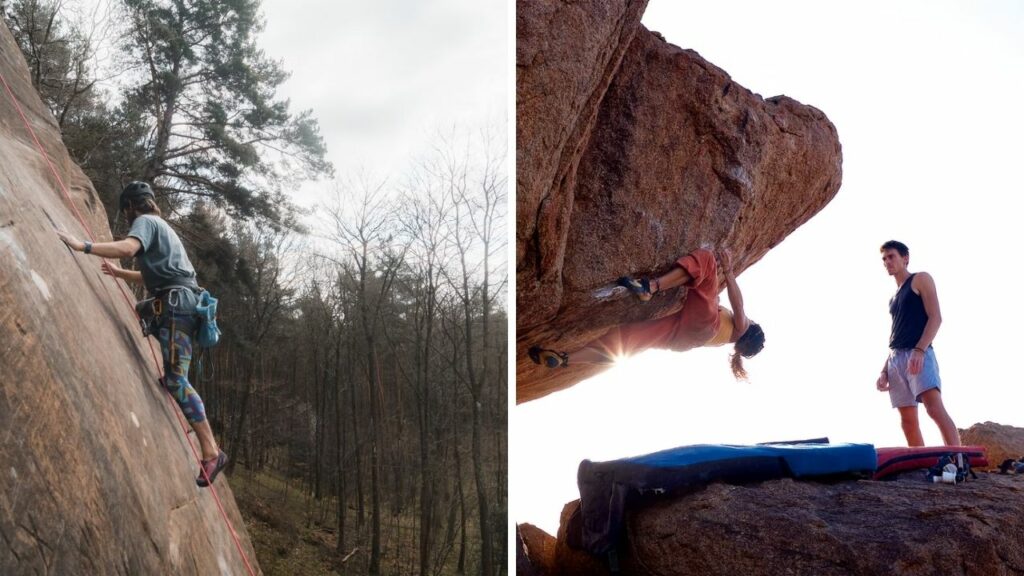

Slabs are the opposite of overhangs. Overhangs, as you know, are slopes with an angle of more than 90°. So, slabs are the slopes with an angle less than 90°.

On an overhang, you use your core, fingers, and toes to hold onto the rock holds. For slabs, you’re essentially climbing a really, really steep hill. Ascending up less-than-vertical rock faces requires intricate balance, footwork, and complete control of body movements.

In theory, both can be challenging and dangerous, but that’s the thrill of climbing. So, why love for one and hatred for the other? It turns out it has very little to do with the difficulty of climbing.

People hate climbing slabs because of the uncertain falls. With overhangs, a misstep and you’d fall on the crash pad below. But with slab climbing, you can hit your head, face, or practically any other body part on the holds while falling.

And then there are the dreaded friction slabs where there are no predefined hand and foot holds, so you rely on frictional force alone. Does that mean you shouldn’t try friction climbing? Definitely not – I gotta lot more to tell you, so don’t assume anything just yet!

What are low-angle and high-angle slabs?

Let’s first get our terminologies straight.

You already know three rocks you can climb – an overhang (angle over 90°), a vertical, and a slab (angle less than 90°).

Within slabs, there are two types – low-angle slabs and high-angle slabs. Low-angle slabs have an angular range of 50 to 70° approaching vertically. This makes them relatively easier to climb. Experienced rock climbers can climb many low-angle slabs quickly using a combination of ‘frictioning’ and ‘smearing’ techniques.

While the falls from low-angle slabs can still be fatal, they’re nothing compared to high-angle slabs. These slabs with a vertical face angled 80° or beyond are arduous and super dangerous.

Why do people hate slabs?

While I have given you the gist of it already, let’s see the whole picture. So, slab climbing looks dangerous for two main reasons. First, the falls are unexpected and scary at first.

Second, the falls are hazardous because if you fall high enough from a slab, you’ll get hit multiple times, scraping various parts of your body against the rocks.

Another big reason is how different it is from overhang climbing. After climbing overhangs and vertical walls for some time, you develop certain habits and reflexes, most of which are fundamentally different from slab climbing.

For example, my reflex allows me to position myself to effectively grab the hold with the side of my feet quickly. It serves me well with overhangs, but it could lead to a pretty hard fall on a slab.

Should you try slab climbing?

Despite the prevalent fear, you should get into slab climbing if it interests you even a bit. It’s fantastic and helps you develop stamina and footwork, core strength for balance and stabilization, and improve overall body coordination.

Beginners need to climb various angles before settling in with their preferences. It’s easier for newbies to get into slab climbing than it is for intermediate-level overhang climbers.

To get started, I recommend indoor slab climbing as it’s considerably safer. The outdoor one will be a brutal experience for beginners.

1. Are slabs harder or easier than overhangs?

Slabs are generally easier than overhangs, but they can be harder for some climbers. You need better balance, sometimes smearing, and friction for slabs. Climbing slabs require more technical knowledge and less physical abilities than overhangs.

2. How to fall safely on slabs?

Falling safely from slabs is tricky but doable with practice. If you’ve gone outdoor bouldering before, then you’ll be familiar with the procedure. The basic idea is to push yourself away from the rock as cleanly as possible to avoid getting hurt.

Here’s how it’s done:

- Spot the fall zone: Look down and check for obstacles. Move around to avoid hitting one accidentally.

- Launch yourself in the air: With overhangs, you can just let go and fall without obstacles. In slabs, however, letting go would mean cuts and bruises. Instead, you have to push yourself away from the wall as far as possible. Then when you make the push, keep your neck muscles in sync with the motion to avoid whiplash.

- Stick the landing: Finally, bend your knees and roll your legs in the air to absorb the impact during landing.

3. How to climb slabs properly?

Climbing slabs, as you now know, is different from ascending overhangs. It’s less of a technique and more like a series of coordinated movements or steps. Here’s how it’s done:

- Start with your prominent foot: Putting the entire body weight on it would increase friction and give you a better hold.

- Positioning your foot: Pay attention to your footing. Sometimes we automatically use the side of our feet to grab hold because that’s how overhangs are done. But with slabs, you grab the hold with the big toe, requiring good foot placement and footwork. Keep your toe in line with your heel at all times.

- Use your palms: Don’t use your fingers to grab hold. Use your palms with fingers facing down instead. It’ll increase the frictional force and let you stay on longer.

- Use your heels: You can move your heel down to increase the contact surface. This works well on low-angle slabs.

- Positioning hips: Move your hips away from the wall to get a better angle. Due to gravity, our body is pulled away from the wall when our hips are close to it.

Ps…don’t rush while ascending steep slabs. Climb slowly but confidently to coordinate full-body control and maintain balance.

4. How to become better at slab climbing?

The best way to get better at slab climbing is to keep practicing. It’s easier to assume you can do slabs just because you’re great with overhangs, but that’s not the case. Don’t let that fool you into choosing higher grade slabs for practice.

To improve your slab climbing skills, start with lower grades and climb as many as you can to learn the basic techniques. Focus on foot placement and slowly shifting your body weight to balance your way to the top.

Practice coordination exercises to work on maintaining balance and stabilizing the core. For example, stand close to a wall with your toes and nose touching the wall. You’ll realize it’s harder to move your heels without disrupting your core balance.

What is smearing in rock climbing?

Smearing is a technique in rock climbing that uses friction between the sole of your shoe and the rock to provide support. When you put your weight into it and press your shoe against the rock hard enough, the friction lets you climb a rock wall without using holds.

It’s a nifty technique that requires a lot of practice to master. You need perfect balance and control of your body and good footwork to smear-climb a rock wall. Smearing is used chiefly during slab climbing, especially for friction slabs without traditional holds.

It’s a misconception that you need a lot of strength to “push your weight,” that’s not how friction works practically. Of course, you need some strength, but proper technique and balance are the keys to smearing.

Ps…make sure your shoes are squeaky clean before you try smearing.

1. How do you smear on a slab?

The right way to smear is the same as I explained about climbing slabs earlier. The only difference is that you need to be more precise and swift this time.

There are no hand and foot holds to grab onto, so you should train your core and apply steady pressure in a stable position. And when you move up, your feet should change their position very quickly to avoid getting thrown off balance.

2. Smearing Tips for Beginners

- Your core must always be in the center of your body during steady positions. Make sure your feet are spread as wide as your shoulders.

- Avoid leaping or overdoing anything, especially on slabbier faces. Climb slowly with small movements (smears) for balance and coordination.

- Make sure your foot is perpendicular to the rock face by lining up your toes and heel.

- Add pressure through the feet by leaning your hips away from the wall. It’s an advanced move that takes practice, as with all good techniques.

Ready, set, balance.